|

to

English Camp page

next page

|

British were popular with

the women

The English Camp in Groningen 1914 – 1918 (part 6)

This is the sixth article in a series on the history of the English Camp in Groningen where 1,500 British service men were interned during the Great War of 1914 – 1918.

Dit is het zesde deel uit de serie over de geschiedenis van het Engelse Kamp in Groningen waar tijdens de Eerste Wereldoorlog

1500 Engelse militairen waren geïnterneerd.

|

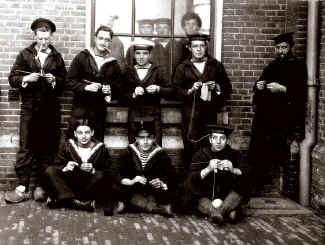

| Picture of some members of the knitting club in the English Camp. They would knit

(for payment) socks, jumpers and other items for the Royal Navy. |

The local people of Groningen were sympathetic towards the internees in the English Camp. In fact, people did not really understand why these men were not allowed to go home. Right from the start, British men were invited by Groningers to call in for a chat or a bite to eat. There was a particularly good opportunity to contact the

British on a Sunday; the Camp was accessible for the public between the hours of 2pm and 4pm. It was a very popular family outing. Contacts were laid with girls from the city, who were very enchanted by these

British ‘war-heroes’. It was not long before the first courtships were reported. Some took off like a rocket, and John Henry Bentham (see previous articles) reports in his diary that ‘after a few months several of our men had married Dutch girls. Anyone who did so was allowed to sleep at his wife’s house, but a guard had to stay in the same house, which rather disrupted romance…’ The

British boys were popular to the extent that local lads jealously referred to ‘English fever’ affecting the girls.

The Groningers generally had a favourable opinion of the British internees. They were referred to as ‘well kept’ and ‘squeaky-clean’. This may have referred more to their exterior than their behaviour, because the girls were warned not to consort with

British if they went out for a night on the town. Nonetheless, quite a few children were born out of wedlock, which was viewed with great disapproval in those days. Even now, 85 years later, there are people who would like to know about this

British grandfather, of whom they often only know a name. Some women were not bothered by all the fuss surrounding the expected child. One mother of such a pregnant girl is said to have remarked that she did not mind at all. The only thing was that ‘the child would be speaking English later’.

Groninger pubs were well frequented during shore leave. Fights would sometimes ensue after excessive alcohol consumption, which required police to attend. Bentham records in his diary, with some satisfaction: “One day, a group of German sailors came into the pub, and the beer pumps were used as offensive weapons. The fight ended when the police entered the pub and returned the men to camp where they were locked up.” He does not tell who won.

On a cultural theme, there was a lot of contact with the Groninger citizenry. Local choirs frequently performed in the camp. Groninger women took part in cultural evenings in the recreation hall in the Camp. They were actors in performances by the Opera Society, the Comedy Society and Dramatic Society. These would sometimes perform in local theatres. Language problems meant that the majority of citizens could only watched the

British at their morning march. The accompanying brass band left an unforgettable impression.

A few local shops complained about British officers who would not pay their bills. They called on the Ministry of War for help in calling in these debts. After consultations between Holland and England, the Camp CO Commodore Henderson would pay the bills, and withheld the money from the officers’ wages.

Next: British football at high level

to

English Camp page

to

English Camp page

|

|