Introduction

Introduction

The Royal Naval Division was a remarkable division in

the British Armed Forces during the First World War. Originating in the Royal Navy, and manned by sailors and marines, the division was incorporated into the Army in 1916. Illustrious figures served in it, such as

the poet Rupert Brooke, Bernard Freyberg (the future governor-general of New Zealand) and the author and later parliamentarian Alan Herbert, but also Edwin Dyett, later executed for cowardice. Two locations along the Western Front feature monuments to the division, and the one at Gavrelle, near Arras, is as extra-ordinary as the division was.

Intrigued by some abbreviations on gravestones, my research into traces of the division started in The Hague, although Groningen might have been better. The anchor was the lead in searches, partially on location and in part virtually, through Internet and books. It led to Antwerp, Gallipoli, the Somme, Arras, Passchendaele to end in London.

The result is represented in this article, which shows the deployment of the Royal Naval Division in a larger context, rather than a very detailed description of combat engagements.

The story is a personal vision and does not intend to be a history of the Royal Naval Division. It became personal even more when it transpired that events in the village of my birth, Moerbeke-Waas, played a small role.

|

|

Royal Naval Division Insignia |

Kerkhoflaan Cemetery, The Hague

Kerkhoflaan Cemetery, The Hague

Cemeteries along the Dutch North Sea coast, such as in towns like ’s- Gravenzande, Noordwijk and The Hague, contain a small number of British war graves with casualties from the First World War. They are there, joined by casualties from the Second World War under the Cross of Sacrifice.

Are the Second War casualties mainly pilots, the dead from the Great

War tend to be sailors, some of whom have remained unidentified and have found a final resting place in a mass grave. Their number, including the unknown, does not exceed 100. A small number, when compared to the casualty list from the Western Front.

This is also the case on the Municipal Cemetery Kerkhoflaan in The Hague, at Scheveningen. The small plot with war graves consists of a memorial stone on the mass grave for the 22 naval personnel, with a few rows of individual graves for another 33 casualties.

The mass grave contains shipmates from three armoured battle cruisers, torpedoed off the Dutch coast on 22 September 1914. These were HMS Aboukir, HMS Cressy and HMS Hogue.1)

The memorial stone is inscribed with an anchor and a world globe, crowned by a wreath of laurels. Emblems of a navy which ruled the seas of the whole world. Rule, Britannia! rule the waves.

Not exactly proved correct on 22 September 1914, as shown again later on during World War I.

|

Memorial to the 22 casualties from the Cressy, Aboukir and

Hogue

on the Kerkhoflaan Cemetery in The Hague

Click on the picture or here

to view an enlarged version |

The Kerkhoflaan Cemetery also contains two British war graves which appear to be indistinguishable from others with the inscriptions of an anchor and a globe on the gravestones.

One is the grave of ‘Able Seaman G.M. Davis RNVR,

Benbow Battalion R.N.D.’ and the second that of ‘Lance

Corporal RMLI, P.E. Rayner, Royal Naval Division’ (see pictures below). A little research showed the connection: ‘RNVR’ stood for Royal Naval

Volunteer Reserve, which was formed before the First World War. ‘RMLI’ stood for Royal Marine Light Infantry, the British marines. Both were naval units which combined to form the Royal Naval Division (RND).2)

|

|

|

Graves on the

Kerkhoflaan Cemetery in The Hague |

Davis and Rayner both died in 1918 gestorven and did not fall victim to the maritime disaster with the armoured cruisers. Why they lie here is not told by their gravestone, nor by the internet database of the Commonwealth War Graves

Commission, but it is not all that relevant to this story. What is of relevance are the inscriptions of the anchor and the globe, particularly as they frequently feature on gravestones on British war cemeteries along the Western Front.

Like along the River Ancre, a tributary to the Somme, or around Gavrelle, east of Arras. Those could surely not have been sailors, washed up ashore, hundreds of kilometres inland. The Royal Naval

Division was not a normal naval unit, but a very specific division which fought like infantry: sailors in the trenches. They originated from the Royal Naval Brigades, formed in 1914.

The birth of the Royal Naval Division

The birth of the Royal Naval Division

The Royal Naval Brigades were composed from a large excess of naval personnel, like reserve stokers who could not be allocated to a ship of the mighty British navy. There were far more men than could be placed on a ship - numbers varying from 20,000 to 30,000 are quoted - at the outbreak of war, in early August 1914, when reservists, including those from the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve, were called up.

To their great surprise, the reservists and volunteers were formed into two Royal Naval Brigades, which had to act like infantry. They might be needed during the war to conquer enemy ports, or defend naval bases outside the United Kingdom.

The two brigades were later merged with an already existing brigade of the Royal Marines into the Royal Naval Division. Their first commanding officer was major-general Archibald Paris, a marine.

The division was commanded by the Admiralty, and was often mockingly referred to as Churchill’s private army or

Churchill’s little army. From 1911 to 1915, Winston Churchill was

First Lord of the Admiralty in prime minister

Herbert Asquith's cabinet.

The Royal Naval Brigades used naval rankings, naval uniforms and insignia, and observed naval traditions. There was a strong esprit de corps

and the men considered themselves elevated above the common foot soldier. Each brigade consisted of four

battalions, which were named after British heroes of the seas, not numbered like in the army.

The eight naval battalions were called Benbow, Collingwood,

Hawke and Drake in the 1st Brigade and Howe, Hood, Anson and

Nelson in the 2nd Brigade. Junior officers included the poet Rupert Brooke, the son of British prime minister Asquith, Bernard Freyberg and the author Alan P. Herbert. In 1915, Herbert, for instance, held the typical navy rank of Acting Sub-lieutenant in the

Hawke battalion.

The four marine battalions were named after the towns of their depots: Chatham, Deal, Portsmouth and

Plymouth. They were closer to the army, and had army ranks.

|

Emblems of the Royal

Naval Division battalions,

as shown on their monument at Gavrelle |

The Royal

Naval Division at Antwerp

The Royal

Naval Division at Antwerp

The Royal Naval

Division's first military deployment, although not yet functioning as a true division, was at Antwerp in October 1914. It turned into a complete failure. 3)

After the battle on the Marne, the fighting on the Western Front moves north. On 14 September, general Erich von Falkenhayn is appointed commanding officer of the German Army. Later that month, the German Army Command decides to launch an assault on

the Fortress Antwerp. Like Liège, the city of Antwerp was surrounded by a ring of fortifications. German forces, headed by general Hans von Beseler, moved against Antwerp from 26 September.

Churchill, representing the British government, travels to Antwerp on October 3rd to pledge British support. His action is highly questionable. Churchill's priority surely should have lain with the navy and preventing further blunders, like the sinking of aforementioned battle cruisers, rather than going to war at Antwerp.

Thirsting for action and glory, as military historian John Keegan calls it, he sent his own little army to Antwerp, to support Belgian troops.

4)

The marines of the Royal Marine Brigade were directed to Antwerp, followed, on October 5th, by the sailors from the two Royal Naval Brigades, in the hope of bolstering the Belgians' morale. Other British troops were not available at short notice. In spite of the Belgian resistance, the battle of Antwerp was already lost by the time the British sailors arrived.

Contrary to the marines, the reservists from the Royal Naval Brigades were barely trained to be infantry men. Some had fired their newly issued rifles only a few times. Before the outbreak of war, the men of the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve had only been sailors in their spare time.

A combination of amateurism and opportunism was supposed to salvage affairs at Antwerp. In other words,

they were no troops to deployed against the well trained German forces, which included the Marinekorps, the German counterpart of the Royal Naval Division.

|

Sailors of the Royal Naval Division

during the defence of Antwerp in 1914 |

Fortress Antwerp was heavily bombed by the Germans, and on 8 October 1914, the Belgian field army withdrew across the river Schelde into the province of West Flanders. They eventually dug in behind the river IJzer. The British forces too withdrew, with only few casualties, on October 9th and returned home via Ostend.

Some 900 men, mainly marines from the Royal Marine Brigade, the rearguard of the British army, were taken prisoner together with Belgian soldiers by the Germans, when their train was halted at Moerbeke-Waas. 5)

Some battalions in the forward trenches was late receiving the order to retreat, if at all, and missed the trains that would take them away. Some 1,500 men from the First Royal Naval Brigade, mainly those from the Hawke, Benbow and

Collingwood battalions, were trapped when the German ring closed on the border between Belgium and Holland at the Dutch enclave of Zeeuws-Vlaanderen.

With some 30,000 Belgian soldiers, they crossed into Dutch territory. For the remainder of the war, the Britons were interned at Groningen in what became known as the English Camp.6)

7) During this interment, eight of them died. They lie buried on the

Zuiderbegraafplaats on the Hereweg in

Groningen.

|

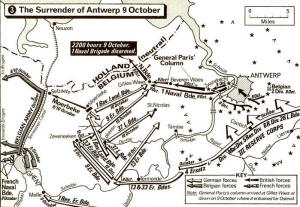

Map showing the final phase of the battle for Antwerp,

the departure of British forces under major-general Paris

and the retreat of the First Royal Naval Brigade into Holland.

Click on the map or here

to view an enlarged version. |

On October 10th, Fortress Antwerp formally surrendered to the Germans. Churchill was mocked, justifiably so, in Parliament for sending the un-trained and poorly equipped Royal Naval Brigades into war for an impossible mission. A year later, things would turn out even worse for Churchill. Once again, the troops from the Royal Naval Division were to be used for a mission with a politically motivated goal.

The Royal Naval Division at Gallipoli

The Royal Naval Division at Gallipoli

Following the engagements at Antwerp the brigades in the

division were re-formed by recruitment. These arrived through the Royal Navy depots in London and several ports on the British coast.

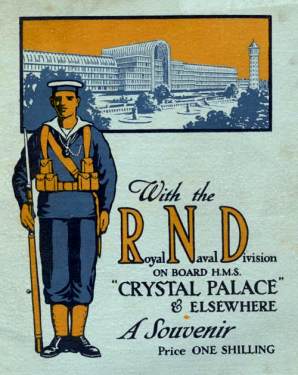

Blandford Camp in Dorset and Crystal Palace in London

were arranged as training camps for the new recruits. In navy parlance, the training camp in London was referred to as boarding HMS Crystal Palace.

|

|

|

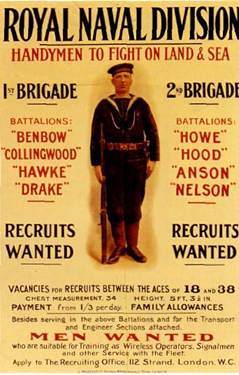

Posters used to recruit men for the Royal Naval

Division early in the war |

After the Western Front bogged down into trench warfare, calls were made by the end of 1914 to start operations on the Eastern Front. This resulted in the campaign at Gallipoli to attack Germany's ally Turkey. The operation would also serve to support Russia, an ally of Great Britain.

Churchill was one of those behind the campaign, and felt that the Royal Navy could neutralise the Turkish fortresses along the Dardanelles in order to clear the route to Constantinople (present-day Istanbul). That proved to be more complicated than originally thought when the British-French fleet sailed into a minefield, and the Turkish fortresses were not all destroyed.

Landing troops were formed to carry out an invasion. As Churchill was involved in the operation at Gallipoli, it was only logical that his Royal Naval Division would play a significant role there.

The British share of the attack force was made up out of the

Royal Naval Division and the professional soldiers from the 29th Division. There was also a large number of Australian and New Zealand troops (ANZAC) as well as a French division. These added up to 75,000 men, commanded by

the British general Ian Hamilton. This number would be augmented further later on.

Rupert Brooke

Rupert Brooke

The poet Rupert Brooke was one of the young British officers who had left for the romantic Middle East full of expectation. It was the region where the Greek heroes of Homer's Iliad had fought at Troy.

Brooke was one of the war volunteers in the Royal

Naval Division. Having joined the Anson battalion in September 1914 he had been at the debacle at Antwerp. He died on 23 April 1915, not on the field of battle, but from blood poisoning resulting from a mosquito bite in transit to Gallipoli.

This was kept hidden from the British public, and Brooke was elevated to the status of martyr and hero. He was buried on the Greek island of Skyros where the Royal Naval Division was waiting on troopships. His grave is still there. The first lines from his patriotic sonnet The Soldier

have become famous:

| |

If I should die, think only this of me:

That there’s some corner of a foreign field

That is for ever England.8)

|

Bernard Freyburg

Bernard Freyburg

Another personality surfaced during the Gallipoli campaign. Parts of the Royal Naval Division conducted a feint attack on the northern side of the peninsula at Bulair. At dusk, landing craft rowed towards the coast to be noticed by the Turks, to return to the ships under the cover of darkness.

|

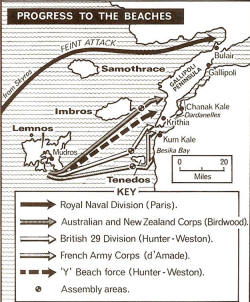

Overview map of the Aegean Sea,

showing the feint attack by the Royal Naval Division at Bulair

(Click the map or here

to view an enlargement) |

Lieutenant Bernard Freyberg from Hood battalion swam from a boat in cold water for a mile to the Turkish coast to light flares, to fool the Turks into thinking that troops were encamped on the beaches. This was part of a successful distraction manoeuvre to divert the Turks from the real landings which took place on 25 April 1915 on the southern side of the Gallipoli Peninsula at Cape Helles.

The division then disembarked at Cape Helles. Benbow,

Collingwood and Hawke-battalions did not arrive until May. The three brigades operated individually rather than in consort as a divisional unit.

2nd Brigade was encamped on the south eastern side of the peninsula, within view of the blue waters of the Morto Bay, and was even added to a French division for a while.

During the following months, the brigades would participate in attacks on Turkish positions towards the hills of Achi Baba above Cape Helles. These engagements have become known as the battles for Krithia. However, the Turkish forces led by the German military advisor general Otto Liman von Sander, were not so easily pushed aside.

In the more general literature on the First World War, the death of Rupert Brooke and Freyberg's action are regularly commemorated in relation to the Royal Naval

Division, leaving the appearance that the division was no longer involved in the campaign at Gallipoli.9)

They were however extensively involved in various fruitless efforts to break through to the north from Cape Helles. The 2nd Brigade for instance was part of a joint force of 30,000 troops which participated in the third battle for Krithia which commenced on June 4th. Like the two previous assaults, this attack too was halted by the Turks.

Considerable losses

Considerable losses

The Royal Naval Division suffered considerable losses in those battles, or through disease in the sub-tropical climate. These losses are estimated at 330 officers and 7,200 men. By June, those losses had mounted up to such an extent that Benbow and

Collingwood battalions were abolished and the men deployed with other battalions. By August, two of the four

battalions of marines suffered the same fate. The Division would no longer be deployed in frontal assaults on Turkish positions.

|

|

In its edition of 31 July 1915, the popular chauvinistic British periodical The War

Illustrated published the above photograph of the Royal Naval Division. in action

10). Its caption read:

| |

‘Charge! The best photographic record of a

charge yet published, showing men of the Royal

Naval Division leaving the trenches in Gallipoli

to attack the Turk by cold steel. On the

extreme left the officer is seen leading the

attack, while the hills in the background are

typical of the difficult country to be traversed

before Constantinople falls to the Allies’.11) |

It would take a few years before the British army command understood that the war could not be won

by cold steel. In spite of courageous fighting with major losses and new landings on the western shore of the peninsula, the Allied force achieved nothing. Constantinople did not fall, and was not even remotely approached.

By the end of 1915 it was decided to withdraw the troops, ending the Gallipoli campaign on 9 January 1916. The debacle meant the end for Churchill as First Lord of the Admiralty, but after a spell of service at the Western Front, where he could conduct war for real, he joined a British cabinet in 1917 as Minister for Munitions. His Little Army would continue to play a role.

The Royal Naval Division in the battle at the Somme in

1916

The Royal Naval Division in the battle at the Somme in

1916

In the aftermath of Gallipoli, a discussion was started on the future of the Royal Naval Division.

The outcome was to maintain the division, but under Army rather than Navy command.

The name was changed to 63rd Division, but the subtitle of Royal Naval Division was kept. Two

battalions of marines and the Anson and Howe battalions made up the 188th Brigade, the other four navy

battalions (Hood, Nelson, Drake en Hawke) the 189th

Brigade. The two battalions of marines became the

First and Second Royal Marine Light

Infantry. Khaki uniforms were introduced, but with navy insignia.

Four regular army battalions were added to the division to bring it up to strength, which made up the 190th Brigade.

For the first time, the Royal Naval Division became a true division with its own artillery and support services. The further history of the division does not substantially differ from other units at the Western Front.

Battalions and Brigades were deployed, fought for one or more days with usually large losses during a battle. They would then be withdrawn to be brought back up to strength with new recruits or men, recovered from

injuries. And back into the fray again.

In May 1916, the division was transferred from the Greek islands to the Western Front. The unit entered France through Marseille rather than the Channel ports. It served in the trenches around Souchez near Arras, the place where the French had fought their bloody battles for the hill with the chapel of Notre Dame de Lorette. In 1916 this part of the Western Front was relatively quiet.

The commanding officer of the division, major-general Paris, was seriously injured and was replaced by major-general Shute. He was not exactly honoured with his appointment, doubted the value of the division in combat and found all those navy ranks and customs just weird.

Shute was not very popular. Following an inspection of the trenches, which raised the general's displeasure with the state of the latrines, Herbert wrote a mocking song with the following closing couplet:

| |

For shit may be shot at off corners

And paper supplied there to suit,

But a shit would be shot without mourners

If somebody shot that shit Shute.12)

|

In early October, the division was directed to the Somme, where British and French troops had been trying to break through German defensive lines since 1 July 1916. 13)

The Royal Naval Division was only deployed by the end of the battle of the Somme in what was to become known as the battle of the Ancre, a tributary river of the Somme. The division was part of the British Fifth Army under general Hubert Gough, and through this deployment would be able to show its mettle.

British supreme commander general Douglas Haig thought he could do with a success in view of the forthcoming conference with the French High Command at Chantilly, and proceeded to exert pressure on Gough. At Chantilly, the allied strategy for 1917 would be discussed.

Haig however was more worried about the meeting with British and French heads of government which would follow the military meeting. There was criticism of Haig's policy from his political superior, Minister of War David Lloyd George. Until October, the Battle of the Somme had not yielded the results expected of it, and there had been no Big Push. Conquering the ridge of the Ancre could counteract some of this criticism.

Douglas Haig is still the subject of lively debates by historians. On the one hand he is portrayed as an ambitious man, out for his own success, a 'butcher' on account of the bloody battles at the Somme in 1916 and at Ypres in 1917, where hundreds of thousands were killed whilst under his command. He could continue interminably with battles that ran into mud.

On the other hand, Haig is regarded as the architect of the eventual allied victory in 1918, which was for the main part due to the British. The British army had learned how to beat the Germans in 1918 through a long process, spanning the years of 1916 and 1917.

It is difficult however to view Haig's decision, to launch another assault at the Somme in November 1916 towards Beaucourt and Serre, in a positive light. Deploying British forces to make a good impression during a conference, also to save his political skin leaves many questions unanswered.

The battle at Beaucourt

The battle at Beaucourt

Since the start of the Battle of the Somme, the front had been deadlocked near Beaumont-Hamel on the left shore of the Ancre River. Serre, one of the aims of the first day of the assault of 1 July 1916 had never been reached.

Hoping for a breakthrough here by the end of the year was

in no way possible by a long way. The rain had turned the battlefield into a mud-bath: Mud prevented any movement.14)

Particularly the area along the Ancre had been turned into a morass. Nonetheless, an attack was launched on Monday 13 November after a dry spell of a few days. 15)

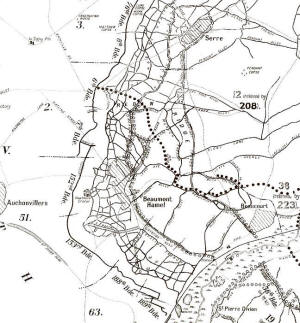

|

Map showing the location of the Battle at the Ancre. The 188th and 189th

Brigades

were part of the Royal Naval Division.

The solid line shows the position of 13 November,

the bold dotted line the final position on 19 November 1916.

(Click the map or here

for an enlargement) |

Of the Royal Naval Divison the 188th and 189th Brigades, those containing the marines and the sailors, attacked along the left shore of the Ancre. The 152nd and 153rd Brigades of the Scottish 51st Highland Division operated to their left - the sailors next to the

Celts.

Of the 188th Brigade, Howe-battalion and the first battalion of marines had to launch the attack, with the Anson

battalion and the second battalion of marines in the second line. Of the 189th Brigade, the Hood and Hawke

battalions launched the attack, with the two other battalions (Nelson and Drake) in the second wave.

The assault began in the dark at 5.45 a.m., with a successful artillery barrage on the German frontline. This was stormed and taken with heavy losses, with the extensive network of German trenches causing confusion and chaos in the forward march. Nonetheless, progress was made and Beaucourt Station was reached.

Hawke battalion was put under heavy machine gun fire and took 400 casualties. By the end of the day, it had virtually ceased to exist.

Re-enforcements of the 190th Army Brigade were sent to the front. The next day, the assault was continued from the station by the 190th Brigade and the combined remnants of the other brigades. The village of Beaucourt was subsequently taken at 10.30 a.m.. By the end of the day, the eastern side of the village could be consolidated.

After two days' fighting, the Royal Naval Division, of rather what was left of it, was relieved on 15 November 1916 by units from the 37th Division.

Beaucourt was bombed by German forces, but remained in British hands. Little was left of the village after the battle, and of the railway station only a piece of wall remained standing. The Scottish 51st Division had succeeded in taking Beaumont-Hamel. As progress had also been made on the right bank of the Ancre, the front as a whole had moved up.

|

|

Ruin of the Beaucourt-Hamel railway station in

1916 |

The battle at the Somme was ended on 19 November 1916. Haig could be satisfied over the results of the last few days, and had received support for the forthcoming talks with government leaders. There was no major breakthrough, just a partial sucess. In spite of Lloyd George's deep mistrust, Haig remained in

command until the end of the war, and was even promoted to field marshal on 1 January 1917.

Once more heavy losses

Once more heavy losses

The Royal Naval Division had shown what it was worth, at the cost of heavy losses. There were 4,000 casualties, of which 1,600 fell during the assault on November 13th and 14h. Whether the severely injured were as satisfied as Haig remains to be seen. But it was not up to the injured to ask such a question.

Theirs not to reason why as Alfred Tennyson wrote in his poem about the casualties, sustained during the senseless cavalry charge by the Light Brigade during the Crimean War in 1854.16)

Herbert lost some friends in the assault, and when he returned to the Ancre area in 1917 - where new men had been positioned - he wrote the poem Beaucourt Revisited.17)

The last two stanzas run as follows:

| |

I crossed the blood red ribbon, that once was no

man’s land,

I saw a misty daybreak and a creeping minute hand;

And here the lads went over and there was Harmsworth

shot,

And here was William lying - but the new men know them

not.

And I said, ‘There is still the river and still the

stiff, stark trees,

To treasure here our story, but there are only these’;

But under the white wood crosses the dead men answered

low,

‘The new men know not Beaucourt, but we are

here, we know’. |

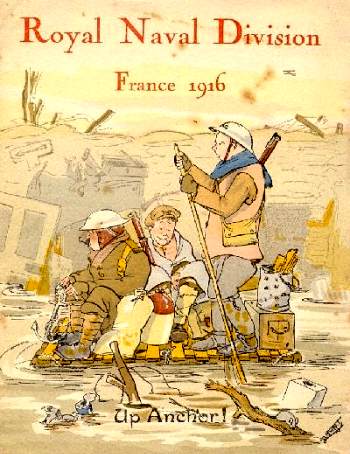

In spite of the losses sustained, the Division issued a Christmas card with a pun – Up Anchor!

– on their performance at the Ancre River. The sailors would be able to use their seafaring skills to survive in the quagmire of trenches. Gallows humour is one way of coping with difficult circumstances.

|

|

Christmas card from the Ancre. The anchor is raised on the left |

Bernard Freyberg once again

Bernard Freyberg once again

During the fighting over Beaucourt, Bernard

Freyberg, commanding officer of Hood battalion, distinguished himself like at Gallipoli. Freyberg came from New Zealand, where his parents had moved to from England.

When war broke out in August 1914, he was in London and immediately joined the British, rather than the New Zealand, army. Freyberg lived through the history of the Royal Naval

Division from Antwerp onwards. Adventurous, determined, athletic (a great swimmer) are a few characterisations of him.

He was injured several times during the assault on Beaucourt and was awarded the Victoria Cross for his actions. A good commander can make the difference between victory and defeat, and Freyberg was such a man.

At the end of the first day of the attack, he gathered those soldiers that were left and led the assault on the Beaucourt Redoubt, shouting: 'Steady, the Naval Brigade'. In the citation for the Victoria Cross this is commemorated as follows:

| |

‘By his splendid personal gallantry he

carried the initial attack straight through the

enemy’s front system of trenches. Owing to mist

and heavy fires of all descriptions,

Lieut-Colonel Freyberg’s command was much

disorganised after the capture of the first

objective. He personally rallied and re-formed

his men, including men from other units who had

become intermixed.

He inspired all with his own contempt of danger. At the

appointed time he led his men to the successful assault

of the second objective, many prisoners being captured.’18)

|

Freyberg's star would rise quickly. 19)

After his recovery in 1917, he would return to Hood battalion, but was promoted to brigadier-general in April at 58th Division. He was only aged 28 by then. His successor was Arthur

Asquith, son of British Prime Minister Herbert Asquith,

although his government by then had been replaced by one led by Lloyd George. Arthur Asquith too would survive the war, although one of his legs was amputated.

|

Royal Naval Division Brass Band in 1916. Wearing the light-coloured trousers

in centre front is Bernard Freyberg, and to his right, Arthur Asquith. |

Edwin Dyett

Edwin Dyett

Under pressure, some people will excel themselves and become a hero. Conversely, others buckle under the strain and come to be regarded as cowards.

The latter fate befell Edwin Dyett, a sub-lieutenant in the Nelson

battalion of the 189th Brigade. He was the son of a Merchant Navy captain, and had joined the Royal Naval Division as a volunteer in the spring of 1915.

Nelson battalion was the reserve in the attack on Beaucourt on 13 November 1916 and was deployed in the second wave. During the fighting, which saw Freyberg declared a hero, a tragedy was also in the making.

Dyett suggested that he had lost the way when he and his men went forward. Dyett was ordered by a staff officer, looking for stragglers on the battlefield, to follow him. But Dyett elected to return to brigade headquarters for new orders, in view of the chaotic situation.

Dyett disappeared from the scene for a while, and when he resurfaced without sufficient explanation he was arrested and indicted for ignoring an order. The staff officer had reported Dyett over the incident.

|

|

Sub-lieutenant Edwin Dyett |

Dyett was court-martialled on 26 December 1916, found guilty of cowardice and desertion and sentenced to death. In his defence, he admitted being neurotic and regarding himself unfit for front duty. He had previous requested a transfer to service at sea.

The recommendation for clemency was backed up by Dyett's division commander Shute, but Douglas Haig endorsed the death sentence. Dyett's execution was to set an example. A British officer could simply not desert his duty.

On 5 January 1917 Dyett was shot at dawn by men from his own

battalion. He was only 21 years of age, and lies buried in Le Crotoy cemetery, near the Somme estuary. His tombstone shows a quote from the New Testament: “If doing well ye suffer

this is acceptable with God”.

Other service personnel from the Royal Naval

Division were sentenced to death during the Great War, but Dyett was the only one to actually be put to death.

By the end of the war, Herbert wrote a book entitled The secret battle which was published in 1919. It was based on Dyett's case. Although Herbert served in Hawke

battalion, he must have known Dyett.

The secret battle recounts the tale of young officer Harry Penrose, a war volunteer, during the battles at Gallipoli and the Somme. Penrose is not an alter ego of Dyett.

The book is not a historical account, rather it

shows what happens when a soldier gradually loses his courage and self confidence. It also demonstrates what the consequences are when this is regarded as cowardice during an attack. Herbert's character Penrose shares Dyett's fate: the final humiliation in a death sentence. Shot at dawn has become an expression, laden with infamy.

Traces around

Beaucourt Traces around

Beaucourt

The former battlefield along the Ancre has been incorporated in the tourist trail - the signs with poppies - along monuments and cemeteries which bear witness to the Battle of the Somme of 1916. Many battlefield tourists follow the road from the Thiepval Memorial along the Ulster Tower, across the Ancre River and the Railway direct to the Canadian Newfoundland Park. To the north of that park stands the monument to the Scottish 51st Division, near the deep cleft, known as the Y-Ravine.

In order to draw in battlefield tourists to have lunch, a sign stands at the junction for Beaucourt (on the D50 road) pointing to the Beaucourt Station restaurant with the text: ‘(63rd) R.N. Division’, the word ‘Café’ and a large anchor, the emblem of the Royal Naval Division.

|

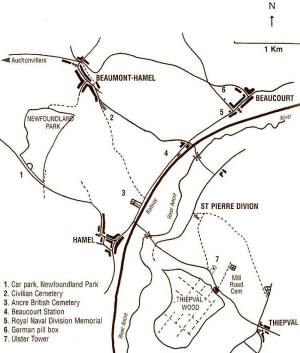

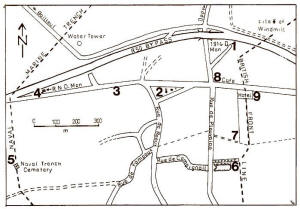

Map

Beaumont-Hamel and Beaucourt

(Click the map or

here

for an enlargement) |

The D50 road was the route, used by the Royal Naval Division

during the attack on November 13th and 14th, 1916, and passes what remains to commemorate the battle along the Ancre to Beaucourt. That is not much. The Ancre British Cemetery, the former Beaucourt-Hamel railway station, the monument to the Royal

Naval Division and the remnant of a German pill-box. Like much of the Somme battlefield, little leaves the impression that fierce battles raged here all those years ago.

The British Ancre Cemetery is a medium-sized cemetery where graves from several battles are gathered. It lies approximately at the frontline of 13 November 1916, when the assault was launched. Originally, the cemetery only contained the dead of the 36th

Ulster and the Royal Naval Division, but casualties of other battles around Beaumont-Hamel were laid to rest here later.

The Ulster Division attacked here on 1 July 1916. The register to the graveyard mentions that 2,540 dead lie buried here, of whom 1,335 are unknown. That is more than half their number and usually indicates that the battle was a ferocious one. Hundreds of gravestones show the inscription of the anchor and the globe.

Two stand together and belong to ‘Able

Seaman G. Patrick R.N.V.R, Anson Battalion R.N.D.’ and

‘Colour sergeant C.R.B. Lane RMLI, Royal Naval

Division’.21)

Both fell on 13 November 1916. These tombstones appear to form a link to the Kerkhoflaan Cemetery in The Hague.

|

|

Graves on the het British Ancre Cemetery |

Beaucourt-Hamel railway station was rebuilt after the war, and remains in situ to date. It is no longer used, and is falling into decay along the road. The Beaucourt Station café stands nearby.

22)

The monument to the Royal Naval Division is in Beaucourt village, elevated above the entrenched road through the village. It was erected in the 1920s. The monument is a white obelisk, which shows beautifully against a blue sky, and a plaque. The obligatory text runs: In memory of the officers and

men of the Royal Naval Division who fell at the battle

of the Ancre, November 13th-14th November 1916.

|

|

The Royal Naval Division monument in Beaucourt |

The Royal Naval Division in the battle near Arras in 1917

The Royal Naval Division in the battle near Arras in 1917

The next major battle in which the Royal Naval

Division was deployed was at Arras in April 1917. This battle became known primarily for the conquest of Vimy Ridge by the Canadians, who have placed their national memorial there.

The conquest of Vimy Ridge was only part of the arranged Anglo-French spring offensive. The French would attack at the

Chemin des Dames – general Robert Nivelle's infamous offensive - and the British would go in at Arras. In the Anglo-French governmental talks, it was decided that the French would determine strategy.

Haig had been bound, under pressure from Lloyd George, to assist the French. The Britons would attack earlier to force

the Germans to withdraw their troops from the Chemin des Dames. After a breakthrough, the armies would march on to finally drive the Germans out of France. That was the optimistic plan at least.

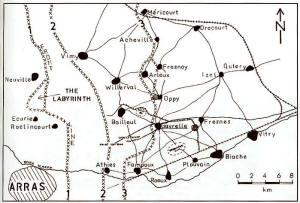

The Britons launched their offensive on April 9th, 1917, and the Third Army, led by general Edmund Allenby, was under orders to proceed to the north and south of the Scarpe River. The 4th British and 9th Scottish Divisions attack to the north of the river.

The first day went well, the Germans were surprised and the aims were achieved. Making some 3 miles of progress in one day was unheard of since battle at the Somme. The front moved north of the Scarpe to beyond the line between Athies and Vimy (line 2, see map below), and even the village of Fampoux was reached.

Progress after that was appreciably more difficult on account of German action. In mid April an attack on the village of Roeux, situated on the Scarpe River, failed and Douglas Haig ordered a break in operations.

|

Map showing the operations of the Third British Army in April 1917 north of

the Scarpe River. The numbers show German defensive lines.

(Click the map or here

for an enlargement) |

On April 16th, meanwhile, the French had launched their attack at the Chemin des Dames, which was a failure from day one. The French demanded however that the British continue their offensive. And thus, fighting carried on.

The Royal Naval Division was ordered to take Gavrelle

and breach the third German defensive line. The non-opular Shute had been replaced as early as February by major-general C. Lawrie.

The attack on Gavrelle was commenced on 23 April and was carried out by the 189th and 190th Brigades. At 4.45 a.m. Nelson and Drake

battalions went over the top under cover of an artillery barrage. The first line of German trenches was quickly taken, and an hour later the attack was ceased at the edge of the village.

The artillery barrage was relocated across the village, which was reduced to rubble. Other

battalions from the brigade were moved forward. House to house fighting led to the taking of Gavrelle, at the cost of 1,500 casualties.

One of the injured was Alan Herbert, the last of the original volunteers from Hawke

battalion who had fought at Gallipoli. Herbert's fight was over; after his recuperation he would not return to the Western Front.

The next day, the Germans launched a counter-offensive to retake Gavrelle, starting with an intense bombardment. This was beaten off, and on 26th April, the attacking

battalions were relieved. In the Official

History of the Great War the following is printed with regard to the fighting at Gavrelle between April 23rd and 25th:

| |

‘Full justice has not been done to the

achievement of the 63rd Division, because the

details of the street fighting in which it

showed skill and determination are to intricate

for description. The division had taken 479

prisoners and in defeating the counterattacks

had obviously inflicted heavy loss upon the

enemy.’23)

|

The relief troops had to continue the British attack towards the windmill, a reinforced German position northeast of the village. This task was allocated to the marines and the Anson

battalion of the 188th Brigade, who had not been deployed on April 23rd.

The attack started at 4.25 a.m. The second battalion of marines succeeded in taking the windmill, and hold it as an enclave in German-held territory. That was the only British gain, because after a day of bloody fighting, the situation was basically unchanged from the start. That did not change until the troops of 31st Division relieved them in the night of April 30th.

|

|

Artist's impression of the fight for the windmill at Gavrelle |

The publication The War Illustrated featured in its edition of 7 July 1917 a drawing of the fighting for the windmill. The flowery description ran:

| |

‘Stubborn contest for the possession of

Gavrelle Windmill, one of the many heroic

episodes of the fighting along the Scarpe. Mr.

Philip Gibbs, in his vivid account of the final

capture of the mill by the British, says that

again and again “the old windmill beyond the

village changed hands. Eight times the Germans

who had dislodged our men were cut to pieces or

thrust out, and then our men finally held it.”24)

|

More heavy losses

More heavy losses

The fighting at Gavrelle had claimed 3,000 casualties from the Royal Naval Division. In particular, the losses of the Royal Marines Light Infantry were severe, with 850 casualties and many dead, including the commanding officer of the first

battalion of marines, lieutenant-colonel Cartwright.

Virtually all the remaining reservists of the original Royal Naval Division lost their lives at Gavrelle. They were the veterans who had survived the fighting at Gallipoli and at the Ancre. The division was rebuilt however, and on 24 September 1917 the

Royal Naval Division would be withdrawn from this part of the front to be deployed at Ypres.

The battle around Gavrelle was to continue in spite of heavy German resistance. Gavrelle formed a bulge in the British frontline, so in May, combat ensued to the north and south of the village, for the villages of Oppy and Roeux respectively, to straighten out the frontline.

The French offensive at the Chemin des Dames was a disaster, and was halted in May. On May 15th, Nivelle lost his post of French supreme commander to general Philippe Petain. The British had also ceased making progress and halted their operations. Haig was no longer bound to his arrangements with the French, and focused his attention wholly on Ypres.

The much-vaunted offensive near Arras, started on April 9th, fizzled out eventually. Only the Canadian triumph, in the conquest of Vimy Ridge, lives on. Remains the question, what was the point of the ferocious fighting by the Royal Naval Division at Gavrelle. The consequences for the division are probably best summarised in the saying: "Action without vision is a nightmare".

Traces in and around Gavrelle Traces in and around Gavrelle

Little remains to be seen in Gavrelle. The monument to the Royal Naval Division is located at the western side of the village, near the sliproad from the N50 dual carriageway, linking Douai and Arras. It sits in a triangular piece of land between the N50 and the village main street. The monument is not exactly located in a quiet spot, due to the proximity of the fast moving traffic on the N50.

|

Gavrelle Town Plan

(Click the map or hier

to see an enlargement) |

The memorial was inaugurated in 1991, and is the most remarkable British war monument on the Western Front. It consists of an anchor, weighing 3 tons, the emblem of the division, surrounded by a broken wall, which symbolises the ruins of the village of Gavrelle. It can be regarded as a monument both to the service men and the civilians who had to live through the battles.

At the time of the war, Gavrelle's houses were built of red bricks. The anchor came from a British naval vessel which had sunk at Milford Haven. The naval emblems of the division have been affixed to the walls. Stones and grenades have been piled along the walls surrounding the memorial. Of the windmill, subject of such ferocious fighting on 28 April 1917, nothing remains today.

|

|

The unusual Royal Naval Division monument at

Gavrelle |

The small Naval Trench Cemetery is another memory of the actions of the sailors-soldiers here. It lies in the middle of a field, but can be reached along a path. It contains only 59 graves, of which only half contains dead from the Royal Naval Division. One of the gravestones carries the inscription: Anchored on God’s Wide Shoreline.

In March 1918, it was a trench, not yet cleared, according to an account by a soldier from the British 56rd

(London) Division:

| |

‘That was a terrible part of the line, in front of Oppy Wood and

Gavrelle. The Royal Naval Division had attacked there the year before, and their

bodies were still hanging on the wire where they’ d been caught up. The trench

that was now our support line was called Naval Trench.’25)

|

Other dead from the Royal Naval Division lie in other cemeteries in this area, such as the Point-du-Jour Cemetery. Point-du-Jour formed the end of the ridge which is now known as Vimy Ridge.

Point-du-Jour was taken on the first day of the British offensive on 9 April 1917. The division departed from this position on April 23rd, for their attack on Gavrelle.

The Point-du-Jour Cemetery is along the busy N50 road, but there is no exit nearby. The hill can be reached from the south, via Athies village. There are 794 graves, of which more than half are unknown dead. The monument to the 9th Scottish Division was recently transferred to the cemetery, which used to stand a little

further on.

A little park was created which cannot be called quiet, due to the heavy traffic. The final resting place of the men of the

Royal Naval Division

, who died in this area is not very peaceful. There are some very young sailors. One row in plot III. F. 14, all from the Royal Naval Volunteer

Reserve (see picture), starts with Able

Seaman H. Roach, aged 20, with Able Seaman H.

Wilkins next to him, aged only 19 years.

|

Four sailors' graves from the Royal Naval

Division in the

Point-du-Jour cemetery near Gavrelle |

The Royal Naval Division in the third battle at Ypres in 1917

The Royal Naval Division in the third battle at Ypres in 1917

On 31 July 1917 the British army launched the third battle at Ypres, also called the battle for Passchendaele, after the village where the assault was finished. Haig thought he could finally force a breakthrough, and deployed every available division from the British Empire to achieve that goal. The offensive was larger than the battle at the Somme in 1916.

The German defensive position east of Ypres consisted of a number of lines, including Flandern I, II and III

Stellungen. The position bent, but did not break. The commander of the Fifth Army, general Hubert Gough, was replaced in September by general Herbert Plumer of the Second Army, but he too failed to deliver the much desired breakthrough for Haig.

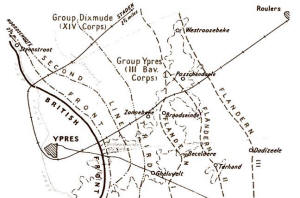

|

Map showing the German Flandern I, II

and III Stellungen east of Ypres

(Click the map or here

for an enlargement) |

The shot up ground and copious rainfall turned the battlefield into a huge quagmire. British, New Zealand and Australian divisions literally fought themselves to death here.

By late October, the Canadian corps of general Arthur

Currie, under protest, would launch a final attempt to conquer Passchendaele village. This part of Third Ypres is known as the second battle of Passchendaele

and lasted from 26 October until 10 November 1917. The Canadians would attack in three steps, progress 500 metres in every stride, and then pull in the artillery.

The Royal Naval Division was tasked to attack alongside the Canadians. The division was to cover the left flank of the Canadian advance. Much like at the Somme, the division was deployed in the final phase of a battle in a quagmire. And like at the Somme the sailors had to endure mocking asides that they, in view of the conditions, would be completely at home. Richard Tobin of Hood

battalion describes the scene:

| |

‘Then, when you got up to the Front, there was no front line to

speak of, just a series of posts scraped in the mud. A machine-gun crew here, a

few riflemen there, further on a Lewis-gun crew.’26)

|

On 26 October at 5.40 am, the Canadian divisions launched the attack for Passchendaele. The first

battalion of marines and the Anson battalion of the 188th Brigade attacked at the same time. Like during previous days, it was raining. A few hours later, Anson

battalion took Varlet Farm, a reinforced German position midway between Poelkapelle and Passchendaele.

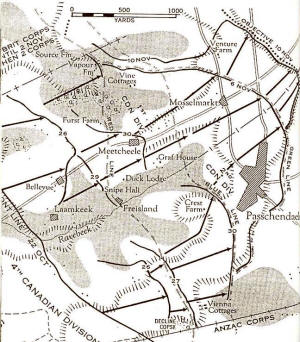

|

The march for Passchendaele.

The black lines show, with dates, the stages of the advance.

The area reached by the Royal Naval

Division is shown on the top left of the map.

(Click the map or here

to view a larger version) |

The area had to be fought over metre by metre in the following days. The mud-bound fights east of Varlet Farm symbolise in miniature what the whole Third Battle at Ypres had been like. Mud in which men would sink and drown. Mud which clogged guns and machineguns, rendering them useless.

On October 30th, the second step was taken and the 190th Brigade attempted, with regular army soldiers, to proceed through the mud towards the Paddenbeek River. One of those

battalions was the 1/28th (County of

London) Battalion, better known as The

Artist’s Rifles.27).

It was their baptism of fire in the war. Of the 470 men who went on the attack, 350 became casualties, of whom 170 fatalities. Most of these were never found, and their names are listed with the missing on the Tyne Cot Memorial.

On 4 November, the 189th Brigade's marine

battalions had their turn. The Hood and

Drake battalions conquered Sourd Farm, another German position near the Paddenbeek River. The German Ernst Jünger

fought on the opposing side, and would tell the story from the German perspective.

28)

|

|

The mud-bath of Passchendaele in November 1917 |

Less than 1 kilometre of territory was gained in the days that the Royal Naval Division fought at Passchendaele, at a cost of 2,000 casualties. The dead lie buried, if they were ever found, among the many other British dead on the Poelcapelle British Cemetery and the Passchendaele New British Cemetery.

On November 6th, the Canadians were finally to take the ruins of the village of Passchendaele. On November 10th, an attempt to progress further was made, but the Third Battle at Ypres was ended by Haig. The Royal Naval Division was withdrawn from the frontline on that day.

The conquest of Passchendaele had claimed some 16,000 Canadian casualties, creating a vulnerable bulge in the

salient at Ypres. In total, the third battle at Ypres had claimed 245,000 casualties on the British side. The terrain gained during this battle was lost to German offensives in the spring of 1918.

‘The point of Passenchendaele defies explanation.’29)

John

Keegan writes. Many historians have tried to explain this mystery, and will continue to do so, in view of the on-going series of publications about this battle. The titles of the books show how difficult British authors find it to deal with the subject. Philip Warner, in 1987, published a book called: ‘Passchendaele, The Story Behind the

Tragic Victory of 1917’.

The focus of the final phase of Third Ypres is on the Canadians, who were in the vanguard. A simple plaque was unveiled on 26 October 2007 at Varlet Farm to commemorate the contribution by the Royal Naval

Division. This was part of a major ceremony to remember the attack, 90 years before.

30)

The text on the plaque runs: Varlet Farm, Poelkapelle, Captured by

men of the 63rd Royal Naval Division, 26th October

1917. The anchor is there, naturally. The fields around the farm frequently give up ammunition and objects, silent witnesses to the battle fought here.

|

Objects and grenades found on the former battlefield around

Varlet Farm, exhibited in a barn at the farm |

The Royal Naval Division in 1918

The Royal Naval Division in 1918

Also in 1918 the Royal Naval Division would be involved in a lot of fighting, but none as iconic as the battles at Beaucourt, Gavrelle or Passchendaele. The period of trench warfare on the Western Front was over. The

mobile war started on 21 March 1918 with the German spring offensives, in which the allied had to yield, to end with the final offensive from the allies, also called the last 100 days, until the Armistice on 11 November 1918.

As the war went on, the navy content of the Royal Naval Division decreased. Casualties, for lack of navy recruits, had to be replaced by infantry men. In 1918 another two naval and one marine

battalion were abolished, leaving 5 out of the original 12 battalions of 1914 by the end of the war.

Nelson battalion was abolished in March 1918, and in May the second

battalion of marines. 189th Brigade remained the sole brigade with exclusively naval

battalions, namely Drake, Hawke and Hood.

Reductions in the strength of the divisions happened across the British army for a lack of soldiers. By 1918, a division consisted of only 9

battalions, as opposed to the customary 12.

After Ypres, the Royal Naval Division was incorporated into the Third Army, now commanded by general Julian Byng. On 30 December 1917, the division found itself west of Cambrai, near Flesquières

on a ridge which became known as the Welsh Ridge, and did not get a peaceful New Year celebration there. The hill was a bulge in the British frontline, a part of the Hindenburg line taken

from the Germans after the battle for Cambrai in late November 1917.

The Germans decided to straighten this vulnerable bulge so the Royal Naval Division was on the defensive for two days, rather than on the attack. It was a localised trench battle, which claimed many casualties. As a result, Hood

Battalion had to be withdrawn from the frontline on New Year's Day 1918.31) This explained why a row of gravestones, showing anchor inscriptions, features on

Flesquières Hill British Cemetery.

Even more ferocious was the Kaiserschlacht, the German offensive launched on 21 March 1918. The division was to the north of the attack front south of Cambrai. In the week leading up to the major offensive an artillery barrage was launched, in which many mustard gas grenades were fired.

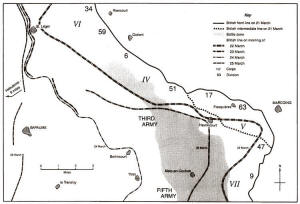

|

The position

of the Royal Naval Division (no. 63) in the Cambrai bulge in the winter of 1918

(Click the map or here

to view a larger version) |

The Royal Naval Division was also gassed, but remained on the frontline in spite of 2,500 casualties. 32)

Like the other divisions of the British Third and Fifth Army, the Royal Naval Division had to fight its retreat when the real German offensive started on 21 March. The Germans now did take the Flesquières salient.

Withdrawing further, the division fought at Bapaume on March 24th and 25th, and on April 5th at the Ancre, well known territory for the old stagers of the division left alive. The British armies had to yield a lot of terrain in March and April, but were able to hold at Amiens. Gough's Fifth Army was practically annihilated.

When the balance swung in the allies' favour, the Royal Naval Division took part in the second battle at the Somme on August 21st - 23rd, the second battle for Arras on September 2nd and 3rd, and the September battles to breach the Hindenburg line. The division crossed the Canal du Nord to take Cambrai with the Canadians on October 8th.

The Division had its final act of war in the march in Picardy, crossing the Grande Honnelle river on the border between Belgium and France. The war ended for the Royal Naval Division in Belgium, the very place where it had all started in 1914. On 11 November 1918 the division was at Saint Ghislain, at that time a village west of Mons, now part of the conurbation of Mons. The name of that city still rings magical in British war history, as it was there that the British fought their first battle with the German army on 23 August 1914.

The end of the Royal Naval Division

The end of the Royal Naval Division

The Royal Naval Division was finally abolished in April 1919. This happened during an official parade at Horse Guards Parade in London. This parade was taken by the

Prince of Wales33)

in

the presence of Winston Churchill, who had founded the division. Like the division itself, he had moved from the Navy to the Army and had become Minister of War. Churchill would also write a preface to the book ‘The Royal Naval Division’ by Douglas Jerrold from 1923 about the history of the division. Jerrold served in the

Royal Naval Division and fought at Gallipoli and in France. The book is as good a memory as a physical memorial. 34)

|

The Royal Naval Division was and would be remain a unique war formation. But it was one that had fought in the Great War from beginning to end in all major battles of the British army. And one that had gained a good reputation. The division suffered total losses - killed, injured or missing - of some 47,000 men, of whom 37,000 on the Western Front. Six Victoria Crosses were awarded to the division. It is slightly ironic that more than 40 percent losses, incurred by the Royal Navy during World War I were sustained in the trenches.

|

|

Memorial to the Royal Naval Division in London |

In 1925 a monument was erected outside the Admiralty building in Whitehall, the centre of the British naval forces.35)

It is a fountain, mounted by an obelisk. The monument was moved in 1939 due to the onset of World War II, but was reinstated in 2003 in its original location. It carries a patriotic inscription with the text from a poem by Rupert Brooke:

| |

Blow out, you bugles, over the rich dead

There’s none of these so lonely and poor of old

But, dying, has made us rarer gifts than gold

These laid the world away, poured out the red

Sweet wine of youth, gave up the years to be

Of work and joy, and that unhoped serene

That men call age, and those who would have been

Their sons they gave, their immortality. |

The inscription shows the popular enthousiasm of the English youth in 1914, who would give their lives for their

homeland. A few years later, another English poet, Wilfred Owen, would rephrase it in a completely different fashion in the lines: The old lie: Dulce et decorum est, Pro

patria mori.

My search for traces of the Royal Naval

Division cannot end with such a piece of bombast by Rupert Brooke. He was part of the division, but never fought real battles in the rain and mud. Nobody knows if he could have lived through such battles, or whether he, like Edwin Dyett and other junior British officers, would have buckled under the strain.

The poems by Alan Herbert provide a more fitting conclusion to this tale. He admittedly wrote the text during the Second World War, but probably thought back to his time in the trenches at Gallipoli and the Western Front during the Great War. The enthusiasm for war of 1914 was over, but the British kept on fighting until the German army finally gave up the battle.

The text of Salute the Soldier36)is still topical, and runs as follows:

| |

Hail, soldier, huddled in the rain,

Hail, soldier, squelching through the mud,

Hail, soldier, sick of dirt and pain,

The sight of death, the smell of blood.

New men, new weapons, bear the brunt;

New slogans gild the ancient game:

The infantry are still in front,

And mud and dust are much the same.

Hail, humble footman, poised to fly

Across the West, or any, Wall!

Proud, plodding, peerless P.B.I.37)

The foulest, finest job of all.

|

The sailors of the original Royal Naval Division would have detested the word soldier, although in fact that is what they were.

Literature references

Literature references

▬

Arthur Banks, A Military Atlas of the

First World War, London, 1975.

▬

Nigel Cave, Battleground Europe, Beaumont

Hamel, Newfoundland Park, Somme,

London, 1994.

▬

Nigel Cave, Slagveld België, Passendale,

De strijd om het dorp, Erpe, 1999.

▬

Philip J. Haythornthwaite, Gallipoli 1915,

Osprey Campaign Series, Oxford, 2000.

▬

Tonie and Valmai Holt, Poets of the Great

War, London, 1999.

Chapters on Rupert Brooke and Alan Patrick Herbert.

▬

Chris McCarthy, The Somme, The day-by-day

account, London, 1996.

▬

Chris McCarthy, The third Ypres,

Passchendaele, The day-by-day account,

London, 1995.

▬

John Keegan, The First World War, London, 1998.

▬

Paul Reed, Battleground Europe, Walking

the Somme, A Walker’s Guide to the 1916

Somme Battlefields, London, 1997.

▬

Paul Reed, Battleground Europe, Walking

the Salient, A Walker’s Guide to the Ypres

Salient, London, 1999.

▬

Paul Reed, Battleground Europe, Walking

Arras, A Guide to the 1917 Arras

Battlefields, London, 2007.

▬

Kyle Tallett and Trevor Tasker,

Battleground Europe, Gavrelle, London, 2000.

▬

Commonwealth War Graves Commission website

▬

Websites about the Royal Naval Division see:

www.royalnavaldivision.co.uk and

www.1914-1918.net/63div.htm.

Notes

Notes

[1]

For a more recent article on the foundering of the battle cruisers read:

Ingmar Seelbach, De ondergang van het ‘Life bait

squadron’, in Wereld in oorlog, Nr. 3, December 2007, p.

4-10.

[2]

In 1914, a British division consisted of three brigades, with four

battalions each of some 1,000 men.

[3]

For an account of experiences by the Royal Naval Division during the battle for Antwerp, read Lyn Macdonald, 1914. Dagen van Hoop,

Amsterdam - Antwerpen, 2005, Hoofdstuk 21.

[4]

Keegan, p. 139.

[5]

Paul Hesters, De beschieting op 9 oktober 1914 en het leven tijdens

de Grote Oorlog in Moerbeke-Waas, 2007.

[6]

For more details: Evelyn de Roodt, Oorlogsgasten, Vluchtelingen

en krijgsgevangenen in Nederland tijdens de Eerste

Wereldoorlog, Zaltbommel, 2000, p. 83-95.

[7]

Read:

Menno Wielinga, De internering van Engelse militairen in Groningen

[8]

Click here for the

complete text of the poem

[9]

For some experiences of the Royal Naval Division at Gallipoli read: Menno Wielinga, De strijd om

Gallipoli, De geallieerde landmachtoperaties op het

schiereiland Gallipoli in 1915 (periode 25 april 1915 –

9 januari 1916).

[10]

This picture features in several (photo)books about the First World War. Adrian Gilbert (World War I in

photographs, London, 1986, p. 64) mentions that the picture is one of an exercise by the Second Royal Naval

Brigade. This holds some truth, due to the narrow trench and the fact that in 1915, photographers did not come this close to the frontline.

[11] JA. Hammerton (Ed.), The War Illustrated, A Pictorial Record of the

Conflict of the Nations, London, 31th July, 1915.

[12]

For the complete text of the mocking poem read: Lyn Macdonald,

Somme, 1916, Amsterdam - Antwerpen, 2003, p. 344-345.

[13]

For some experiences of the Royal Naval Division during the battle of the Somme read Lyn Macdonald, Somme, 1916, Hoofdstuk

24.

[14]

McCarthy, The Somme, p. 148.

[15]

For a more extensive description of the battles, read The

taking of Beaucourt 13/14 November 1916.

[16]

Read website

www.nationalcenter.org

[17]

Click here for

the complete text of the poem

[18]

Cited from Reed, Walking the Somme, p. 78.

[19]

After the war, Bernard Freyberg remained in the British army, which he left in 1937 as a brigadier-general. During the Second World War, he returned into military service and became commander-in-chief of the New Zealand Army. Between 1946 and 1952, he was governor-general of New Zealand. Read: Wikipedia/Bernard_Freyberg.

[20]

Click here for a discussion of the book ‘De verborgen strijd’ [Hidden Battle] and its relevance in the case Edwin Dyett.

[21]

A Colour sergeant ranked above a sergeant in the British armed forces.

[22]

Read www.ensomme.net.

[23]

Quoted from Tallett, p. 52.

[24]

The War Illustrated, 7th July, 1917. Philip Gibbs was a British war journalist

[25]

Quoted from

Lyn

Macdonald, Spring 1918. To the last man, London, 1998, p. 303.

[26]

Quoted from

Max

Arthur, Forgotten Voices, London, 2002, p. 243-244.

[27]

The Artist Rifles was established in 1859 and consisted of volunteers, among them well-known 19th century British artists such as William Morris and Holman Hunt. The unit was even more unusual than that made up of sailor-soldiers. In the first years of the war, it was a training unit for officers, and became known as

1/28th (County of London) Battalion. Many artists and writers, such as Wilfred Owen received their officer's training in the unit. In June 1917, the

battalion was added to the 190th Brigade of the Royal Naval Division as an operational unit.

[28]

Ernst Jünger, Oorlogsroes, Amsterdam – Antwerpen, 2002, Chapter entitled ‘Weer Vlaanderen’.

[29]

Keegan, p. 394.

[30]

See website

www.wo1.be.Varlet Farm is a farm with B&B accommodation. Information is available about the battle at Passchendaele. A collection of battle related objects, dug up from the farm, is on display. See

www.varletfarm.com

[31]

Malcolm Brown, The Imperial War Museum Book of 1918. The Year of

Victory, London, 1998, p. 14.

[32] Martin Middlebrook, The Kaiser’s Battle, 21 March 1918: The First

Day of the German Spring Offensive, London, 1988, p.

110.

[33]

The later king Edward VIII (1894-1972), better known as the Duke of Windsor after his abdication in 1936

[34]

The book has been republished by the Naval & Military Press.

[35]

See

The Royal Naval Division Memorial.

[36]

See:

oldpoetry.com

[37]

P.B.I.: Poor bloody infantry. |