|

|

INTRODUCTION

On reading Donald MacDonald's book on the history of Lewis, I

encountered a reference to the internment of Lewis men in Groningen, and

I decided to conduct a little research into the subject.

In 2002, a Dutch amateur historian, Menno Wielinga, published a series

of 13 articles on this subject in a regional newspaper in The

Netherlands, which serve as the backbone to my story. I have translated

the articles and they are published in English on the website

www.wereldoorlog1418.nl

I would like to express my gratitude to those who went to the trouble of

contacting me, by letter, telephone or email, following my initial

appeal in the Gazette on 27th January 2005. I also would like to thank

the staff in Stornoway Library for their enthusiastic cooperation.

I should point out that all (Lewis) inmates of the camp are now

deceased.

A number of questions remain:

• Are there other men from Lewis (or any other island in the Western

Isles) known to have been interned at Groningen?

• Are there any records, oral, written, photographic etcetera of their

experiences in the camp?

• Did any of them try to escape?

• Were any men employed outside the camp, and if so: where and as what?

I have found the names of 106 inmates from the Isle of Lewis. See:

List of internees from Lewis in the English Camp

in Groningen 1914 - 1918

Guido Blokland

Stornoway

February 2007

ROYAL NAVAL BRIGADE 1914

During the First World War, 1,500 British servicemen were interned in a

camp in the city of Groningen in Holland between October 1914 and the

Armistice in November 1918. This group belonged to the First Royal Naval

Brigade. Many of its men were from the Western Isles, as many had joined

the Royal Naval Reserve (RNR) before the outbreak of hostilities in

August 1914.

|

|

[15]

The Naval Brigade, sent to Antwerp in a last effort to save the city, consisted of men handy enough to build their own defences and brave enough to defend them against any odds. Above are naval ratings who had taken their part in building the timber-lined trenches [...]. The men are carrying cartridge belts for Maxim guns, their principal weapon. This line was held by the Naval Brigade until October 6th [1914], when they were forced to fall back on the inner

fortification. |

[15] The Naval Brigade, sent to Antwerp in a last effort to save the city,

consisted of men handy enough to build their own defences and brave

enough to defend them against any odds. Above are naval ratings who had

taken their part in building the timber-lined trenches [...]. The men

are carrying cartridge belts for Maxim guns, their principal weapon.

This line was held by the Naval Brigade until October 6th [1914], when

they were forced to fall back on the inner fortification.

[2]

The Naval Brigade

Memories of John and Roderick MacKenzie, 13 Grimshader

Submitted by Capt. J.R. MacKenzie (macRuairidh Iain Rob) of 13

Grimshader, now of Inverness.

This was a brigade of naval reservists formed when there was a surplus

of naval personnel. They were mostly fishermen and unfortunately given

the minimum of military training. It was the brainchild of Winston

Churchill who at the time was First Lord of the Admiralty.

They were sent to Antwerp just before that city fell to the Germans at

the beginning of October 1914. They went into shallow trenches hurriedly

dug and were under heavy artillery bombardment until October 9th, when

the Germans overran them. After a time of disorganisation and confusion

they managed to cross the border into Holland. Holland was neutral in

that war. They were subsequently rounded up by the Dutch authorities and

interned in a place called Groningen for the duration of the war.

My father, like most of his contemporaries, seldom spoke about his

wartime experiences, but my brother and I put some pressure on him one

evening to tell us about some of the things that happened. He said that

one of the most vivid recollections was having crossed a bridge, leaving

Antwerp, they heard an explosion behind them and on turning around they

saw the bridge which they had crossed minutes before going up in the air

with nothing left intact.

While wandering around the Dutch countryside they suffered much from

hunger. One evening while walking across a field they came across a lone

cow which was duly shot and served as their first food in days (later on

they were asked to compensate the owner of the cow).

While at Antwerp, they became the Royal Naval Division of the Naval

Brigade. There were many Lewis lads in the Naval Brigade - Iain

Mhurchaidh, of 11 Grimshader; Murchadh Chalum Sheoc from Ranish; Shonnie

Mhallaig from Leurbost and many others whose names I cannot now

remember.

They were posted missing for a few monhs before word got home that they

were interned in Holland. The story goes that "A Bhell", Ian

Mhurchaidh's mother, was working on a "feannaig" (lazybed) on the croft

at the time when someone overheard her repeating over and over again

"interned in Holland, interned in Holland" a reaction no doubt to the

joy that her son was safe although a prisoner.

They had their share of hardships, but things began to ease for them

when they started to receive parcels from home and from the Red Cross.

Some of the brigade were able to escape from Antwerp and make their way

home, one of them being my father's cousin Allan Aonghais Rob (Allan

Sketch).

The whole exercise was almost a disaster as they were ill prepared to be

sent against professional German soldiers. My father was fortunate in

that he had done six months training in the Militia ("as a bhalishe").

It was then every young lad's dream to get into the Militia. It was

usually their first employment and the first money they earned. Many

lied about their age in order to be accepted. My father spoke about

sharing his knowledge gained in the Militia with some of his mates while

travelling by tram and boat to Antwerp. It gives an indication of how

ill-equipped they were. Indeed they were in possession of rifles for

only two weeks before they were shipped out. Some of the lads had had as

little as two days' training with rifles.

It was an ill-thought out concept from the beginning, for which

Churchill was rightly blamed. My father's generation had little time for

him and were delighted when Attlee's government pushed him out in 1945.

Though meagre and belated, the intervention of the Royal Naval Division

at Antwerp had nevertheless helped to delay the fall of Antwerp for some

days, gaining time for other units of the British Army to arrive in

Flanders.

Their losses were relatively few, 57 killed and 138 wounded.

CONTRIBUTION BY MEN FROM LEWIS

[4] Historically, the islands contributed proportionally the largest

number of men, larger than any part of Scotland. Scotland itself is

grossly over-represented when compared to other parts of the UK. It was

no different during the First World War. Out of a total population of

30,000 in the Isle of Lewis, more than 6,000 men had voluntarily joined

up. 1,000 of those never returned. This contribution has not met with

the recognition it deserved, certainly not in the immediate aftermath of

the war. Hundreds of men returned to Lewis, expecting the government to

fulfil its promise of land. A promise that was not met, ultimately

leading to civil unrest and emigration.

[16] The proportion of Royal Naval Reservists within the Lewis

contingent is, on average 52%. On average 1 out of every 7 men in the

island joined up, irrespective of unit; the district of Uig contributed

1 out of every 3 men, 30%. The percentages in the last column below

refer to total population, men as well as women; the percentages quoted

in the lines above refer exclusively to males.

| Parish |

Number

in RNR

|

% service-

men in RNR

|

Total in

services

|

population

in RNR

(%) |

Total population

in 1911

|

|

Stornoway

|

970

|

50%

|

1,948

|

7.2%

|

13,414

|

|

Barvas

|

560

|

53%

|

1,061

|

6.2%

|

9,063

|

|

Uig

|

349

|

53%

|

665

|

15.0%

|

2,326

|

|

Lochs

|

388

|

60%

|

646

|

8.3%

|

4,684

|

| Totaal |

2,267

|

52%

|

4,320

|

7.7%

|

29,487

|

There is great bitterness about the lack of recognition. King George sent a

telegram to a Balallan woman, congratulating her on giving her 4 sons to fight for her country. The King sent no telegram when they were all killed.

If it had not been for the kindness of the neighbours in the village, she would have starved, being blind.

STORIES FROM INTERNEES

[1] Chrissie MacRitchie told me that her grandfather, Angus MacLean of

Shader, had been in the camp. In 1915, he was allowed home on ‘harvest

leave’. This was facilitated by a doctor’s letter, which would state

that the man in question was needed at home. What reasons the doctor’s

gave did not become clear. Her aunt, who was 16 at the time, remembers

that she had to go to see the doctor about the letter. Later on, she was

sitting on top of a cart and could see her dad coming up the road from

town; this happened twice. The lady’s uncle, who was also interned,

spoke of starvation in the camp, with inmates having to eat rats

[2] John MacDonald advised me that seven or eight Uig men were at

Groningen, and another 6 or 7 from Bernera. After the war, one man

(Donald MacLeod) went out to California or Canada. A reunion of Lewis

inmates of Groningen was held at the Caledonian Hotel in Stornoway in

October 1959. The gentleman’s father attended that meeting, with three

others. Angus MacDonald, deceased 1970, formerly of 3 Geshader was

allowed home on leave in 1916. If anyone failed to come back to Holland,

the entire leave arrangement would be cancelled. None did desert. The

inmates had to eat horsemeat in the camp. They were allowed to mingle

with locals. John Morrison studied for the ministry in the camp. Some

went back to Groningen in 1959. There was no resentment towards the

Dutch. None of the camp inmates were thought to have perished on the

Iolaire, which foundered on the Beasts of Holm on New Year’s Day 1919

with the loss of 205 lives.

[3] Mrs MacIver told me that her father, John MacIver, studied

navigation in the camp, and acquired a British diploma for (I think) a

second mate’s ticket. I was shown a copy of this document.

|

[12] These men all came

from Great Bernera and are pictured in the camp

Standing L-R Kenneth Macaulay "Coinneach Ruadh" 12 then 1 Kirkibost,

Donald Macdonald "Domhnall Sheumais" 5 Croir, Norman Maclennan

"Tormod a Ghaidheal" 5 Kirkibost,

Angus Maciver "Aonghas Fhionnllaigh" 7 Breaclete.

Seated L-R Norman Macdonald "Nabard" 15 Hacklete, John Macdonald

"Iain Aonghais Fhearchair" 13 Breaclete and Angus Macdonald

"Krudcher" 13 Tobson"

[information courtesy www.hebrideanconnections.com]. |

[4] Donald MacLeod gave the names of the 7 Bernera naval reservists in the

photograph. Not in order, the names given were of the Bernera internees,

i.e.: Angus MacIver, 7 Breaclete; Kenneth MacAulay, 12 Kirkibost; Angus

MacInnes 20 Kirkibost - his brother, Donald, was a prisoner in Germany

having been captured after the fall of Antwerp; Angus MacDonald, 13

Tobson; John MacDonald, 24a Tobson; Donald MacDonald, 16 Tobson and

Norman MacDonald, 15 Hacklete. Donald said that his grandmother was a

MacDonald from Tobson and all these MacDonalds from Tobson would have

been related to her.

[5] Margaret MacPhail told me: I happen to have a jewellery box made in

Groningen prison camp by a cousin of my mother, Angus Maciver of 7

Breaclete, Bernera who was one of the Bernera men in your photograph

(standing far right) It is inscribed RND Groningen Holland. He later

became a headmaster in Scarp and Leverburgh Harris. The box was made for

Miss M.A. Macdonald ( Mary Ann) who was a relative of Angus Maciver. She

was originally from Bernera but taught at Achmore school until she

retired. I have had it in my possession since 50 years now this week it

has become more important to me! I was told that another man from

Bernera was in the camp John Macdonald, 13 Breaclete, Bernera, not in

photograph, do not have any info of him yet.

[4] Murdo MacKay (RNR) of 13 Aignish escaped from the siege of Antwerp,

and walked to France out of Holland. A Dutch farmer gave him civilian

clothes. He died in March 1917 of illness at Plymouth.

Some islanders were released from Groningen because of illness, to die

at home. One of these was Angus MacLeod, 10 Portnaguran, who died at

home on 24 June 1916. Three of his brothers died in the war, one of them

on the Iolaire.

Several internees died at Groningen, among them:

John Smith, 6 Lower Bayble, died on 18th October 1917 at the age of 39.

John MacLeay, 28 Lower Shader, died on 26th August 1915, at the age of

33.

Donald MacLeod, 4 Gearrannan, died in Groningen in 1916, at the age of

24.

[6] Dave Roberts told me:

I have spoken to relatives of four of the internees. They have provided

very little information. They all said that their relatives were very

reluctant to talk about it. They are all of the opinion that the

internees felt that they had surrendered and had therefore not done

their duty. They probably felt guilty that their brothers, cousins and

friends fought and many died, while they were safe in Holland. They felt

ashamed and thought that other people saw them as having avoided the

war. Someone mentioned that one of the internees was accused of having

slept for four years in Holland - this was a joke, but it must have also

hit a raw nerve! One of the relatives mentioned that some of the

internees worked on farms and a group of them had caught a sheep and

killed it. They were so hungry that they ate it raw, on the spot where

they killed it. Only one relative heard of leave being taken. In the

community the sympathy was for the POWs who had a much harder time of

it.

Kenneth Nicolson had 7 brothers and 4 sisters. He talked very little

about his experiences and his niece never heard him talk of or knew of

any leave he may have had. Four of his brothers served in the armed

forces during the first war. Donald was in the army and died in France.

Murdo was in the navy and drowned in the Iolaire disaster. Kenneth never

married. He lived on, and worked the croft until he was 85, and too

infirm to manage on his own. He died in Timsgarry a few days short of

his 88th birthday.

[7] Callum Buchanan, Malcolm Buchanan's son, said:

My father Malcolm died in 1944, our neighbour Murdo Buchanan died some

time in the 1980s. They did not really speak much of what they went

through

[4] Allan MacKenzie, 13B Grimshader escaped from Groningen and returned

to the UK. Ebenezer MacDonald, 41B Ranish could have been decorated in

the 1920s by the Americans for saving lives on an American ship.

|

|

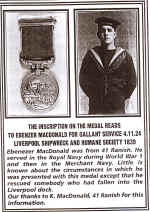

|

[8]From left to right: Roderick MacKenzie (13 Grimshader) - Collage

showing John MacKenzie, made in the Camp) - Ebenezer MacDonald (41

Ranish). The inscription on the medal reads: To Ebenezer MacDonald for

gallant service 4.11.24 Liverpool Shipwreck and Humane Society 1839.

Ebenezer MacDonald was from 41 Ranish. He served in the Royal Navy

during Word War 1 and then in the Merchant Navy.

[4] Liverpool Shipwreck & Humane Society --- Bronze Medal and

Certificate of Thanks to Able Seaman Ebenezer MacDonald, of the Royal

Mail SS Co's, s.s. "Cardiganshire", for rescuing the crew of seven men

of the schooner "Inspiration" of St John's, N.F., which vessel was

abandoned, dismasted and in a sinking condition, in heavy weather in the

North Atlantic on 4th November,1924.

At 7.30am of the above date a vessel was observed flying signals of

distress. The "Cardiganshire" bore down on her and found her to be the

schooner "Inspiration" of St John's N.F., bound from Pernambuco to St

John's in ballast, dismasted, with rudder and rudder post gone and in a

sinking condition. The weather was rough and squally, with a high sea

running.

The Chief Officer was sent away in charge of the lifeboat and brought

back the crew of seven men, who were later landed at Liverpool. The

lifeboat was holed and severely damaged in the process, arriving back at

the ship half full of water."

It is believed that three other crew membes of the " Cardiganshire" who

were decorated were also from the Western Isles : Able Seaman John

MacDonald; Able Seaman John MacLeod and Able Seaman John Martin. |

[8] Mr MacKenzie (son

of Roderick Mackenzie) writes:

"My great regret nowadays is that I did not question (my father) more

about his experiences. He couldn't stand any waste of food, even crumbs,

which we attributed to him having suffered from hunger during the war.

He had a great deal of respect for the Dutch people. He also had a great

deal of interest in cricket, which was unusual for island men. So he

must have learned his cricket while in Holland."

[9] An article in the Stornoway Gazette of 25th January 1918, by Rev DM

Lamont, paints a picture: “They are all young men … who meant to fight

for their country …”. They are in effect prisoners, surrounded by armed

guards. The austere walls of Groningen prison overlook the camp. The

food is poor and inadequate in quantity. At the time of writing, the

‘home leave’ arrangements had been in place for two years, and escapes

were no longer necessary. As indicated above, the ‘compassionate leave’

was sometimes based on rather loose ground.

Rev Lamont describes two escape attempts: one by a sailor, who was

carried out of camp, wrapped in a piece of matting. He made his way to

Flushing, and on to the UK. Another person escaped, walked 20 miles to

the German border and reported to the Burgomaster of the frontier town,

declaring that he’d just escaped from a German PoW camp, and could he

please have a pass for Flushing! Which was duly granted.

Rev Lamont expresses the implicit opinion that lads who had grown up

“among seabirds under Atlantic breakers” would not feel at home in

Holland, “hollow land” with no hills to climb “above the level of

stagnant canals”.

[10] In an interview in November 2005, Margaret Joan MacLeod said:

“My grandfather, Peter MacLeod of 27 Lower Barvas, was in the camp. He

was allowed home on harvest leave twice, one such visit resulting in the

birth of my uncle, Donald Finlay, 9 months later. He taught others to

read and write Gaelic in the camp. Donald Murray, of 47 Lower Barvas,

taught navigation to other inmates. Norman MacDonald, of 25 Upper

Shader, would write home saying that the 'acras' [Gaelic for hunger] was

very bad. Angus MacLeod, of 22 Upper Barvas, was depressed in later

years because he felt that his mother had been paid money for him doing

nothing in the camp. Quite a few of the internees are quoted as having

the "1914 Star" or the "1914 Mons Star".

That ends the net result of the interview. This may seem incredibly

succinct, but mrs MacLeod spent the better part of 3 hours ringing round

the villages of Barvas, Brue and Shader to trace anyone whose ancestors

had told stories of the camp. There were a few, but they were too old or

infirm for me to speak to them. It is very unfortunate in a way, that I

am conducting this research now, in 2005. None of the internees at

Groningen survive, and it appears that they have taken the stories of

their internment to the grave. Their direct descendants are themselves

now very aged as well. The abiding image, in summary, is one of

excruciating boredom and worsening hunger. Several inmates tried to

better their lives through study.

|

|

[4] Some of the returned men of the RND who had been interned in Holland since Antwerp fell in October

1914

(Source: The War Illustrated, 30 November 1918)

|

[11] It was with great interest that I read

your article on the Lewismen interned in the camp at Groningen between

October 1914 and the armistice in November 1918. What caught my

attention even more was seeing my Grandfather’s name mentioned within.

My name is Iain Macdonald and my maternal Grandfather was John MacIver

of North Tolsta on the island of Lewis. I see from your article that you

spoke to one of my aunts regarding this subject.

The reason I am contacting you is to forward a photograph [below] which

was taken in the camp on Christmas day 1915. This photograph shows my

Grandfather 2nd from the right. There are three other Tolsta men in the

picture. They are the Macdonald brothers William (back row far left) and

Angus (back row second right). The other man is John Macmillan (back row

third left) whom I notice you don’t mention in your article. This

information comes from the

North Tolsta Historical

Society.

|

|

|

[13] The man on the far

right is Angus MacLeod, of 22 Upper Barvas. |

[11] My Grandpa was sent

ashore in Belgium with the Royal Naval Division at the beginning of the

war. I think their main purpose was to halt the German advance through

that country. He was with Benbow Battalion. I can remember him telling

me that he was in Antwerp and the place had been deserted.

Unfortunately, the Germans proved too strong for them and they were

forced to the Dutch border where they laid down their arms and crossed

into Holland. He spent the duration of the war in the camp at Groningen.

All I know of his time there was that he studied navigation. He

mentioned to me that he had a pen pal with whom he corresponded in

London. This gentleman would send my Grandpa tobacco and other things to

ease his situation although I think they were fairly well looked after

by the Dutch.

There is a photograph on the Tolsta Historical site

of Lewismen at Groningen. I have downloaded it and attached that also.

The men in this photograph are; Back row left to right, Angus Macdonald

and John Macritchie. Front row left to right are; John Macmillan,

Alasdair MacIver, Angus MacKay, William Macdonald, Angus Morrison and

John MacIver.

I hope this is of interest to you although you may have acquired this

material from another source. I thought it better to send it to you to

make sure you had it. My Grandfather died in 1981 at the age of 88.

[14] The Internees duly returned to Lewis after the Armistice. Calum

Ferguson describes the life of his mother in the Point (or Rubha)

district of Lewis, east of Stornoway. On pages 164 and 165, the author

tells how his mother, a teenage girl at the time, has taken a cart to

town to purchase household goods. It's nearly Christmas, 1918.

"In Percival Square, we saw a group of about a dozen men who had just

returned from internment in Holland and from German POW camps,

celebrating noisily with 'clann-nighean an sgadain' (herring girls).

They were doing a 'danns an rathaid' [street dance] with melodeon

music."

Sources

[1] Chrissie MacRitchie, Glasgow, telephone interview

[2] John MacDonald, Uig, personal communication

[3] Mrs Morrison, Tolsta, personal communication

[4] Donald J MacLeod, Aberdeen, personal communication

[5] Margaret MacPhail, Laxdale, Stornoway, email communication

[6] Dave Roberts, Uig Historical Society, email communication

[7] Callum Buchanan, Brenish, personal communication

[8] Dusgadh 40, North Lochs Historical Society, December 2005

[9] Stornoway Gazette, 25 January 1918

[10] Margaret Joan MacLeod, Barvas, personal communication

[11] Iain MacDonald, personal communication

[12] Hebridean Connections, Ravenspoint Centre, Kershader

[13] Donald Morrison, Barvas, personal communication

[14] Children of the Blackhouse, Calum Ferguson, Birlinn 2004, pp 164,

165

[15] Malcolm MacDonald, Secretary, Stornoway Historical Society,

Personal communication

[16] Loyal Lewis, Roll of Honour 1914-18, Stornoway Library

to

English Camp page

to

English Camp page

|

|